Alcohol is perhaps the nation’s favourite vice, and our collective relationship with it is often under the microscope.

From health concerns over binge drinking to our rowdy reputation overseas, Brits’ alcohol habits regularly make the headlines.

But with plenty of reports suggesting that Gen Z is less interested in drinking than previous generations, perhaps the public health messages have begun to sink into the populace.

Even drinking in moderation poses health risks over the long-term, and it’s all too easy to cross the recommended limit of 14 units per week.

Advert

The long and short of it is that alcohol is a poison. All those bubbly, fun effects – and the not so fun ones – come down to our bodies being impaired by it.

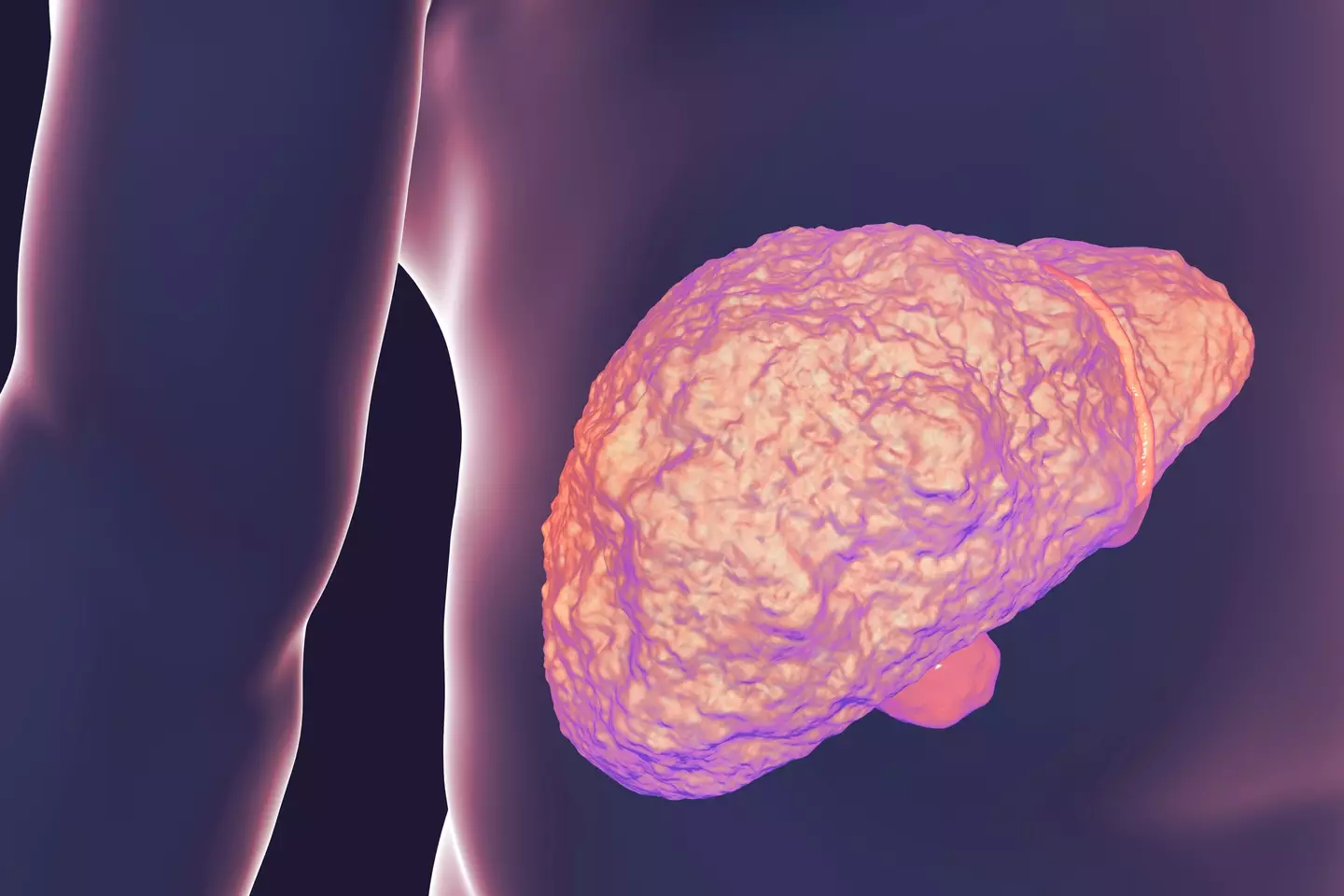

We need to flush it out of our systems, and that’s where the liver comes in. It’s the main line of defence we have against toxins we ingest, and it’s a pretty incredible piece of kit.

Livers are made up almost entirely of the same kind of cell, meaning it can reproduce itself in a way that other, more complex body parts can’t.

We can’t regrow an arm, for example, because our repair mechanisms can’t handle something that complex. Livers, generally speaking, can be regrown even if 90% of one has been removed.

This nifty feature is essential for its function. As the liver filters and processes toxins from the blood, its cells are given a round beating. In a healthy liver, this isn’t usually a problem – the used cells die off, and are swiftly replaced with a fresh wave of willing conscripts.

Prolonged alcohol consumption, especially to excess, can impair the liver’s healing ability. Over time, the liver can become scarred, at which point its regenerative qualities are massively damaged.

Livers can also get overwhelmed by fat cells, generally as a result of a poor diet. While this can happen to non-alcohol drinkers, alcohol can indeed cause fatty liver disease. This condition can also significantly damage the liver’s ability to work and heal itself.

“When alcohol, or ethanol, reaches the liver, the cells of the liver have enzymes that help with the digestion and processing of alcohol,” said transplant hepatologist at Piedmont Healthcare, Dr Lance Stein.

“When alcohol then reaches the blood, that’s when you feel the effects of alcohol.

“As the liver is processing alcohol, it can damage the liver’s enzymes, which can lead to cell death.

“As with any damage to any cell of any organ, there is always a process of healing.”

Short-term damage can typically heal within a few weeks, although drinking regularly over that period can hamper the process. Over the long term, this can lead to cirrhosis, or broad liver scarring.

Dr Stein noted that: “if the damage to the liver has been long-term, it may not be reversible”.

With that in mind, it’s important to be mindful of your alcohol consumption to ensure you’re not overwhelming your liver.

This is a major factor in the 14-units-per-week recommended limit. It’s also recommended that those 14 units are consumed across three or more drinking sessions rather than all at once.

“It’s important to know what you’re drinking because when people mix their own drinks, they’re often using more than the recommended amount,” continued Dr Stein.

“They think they’re drinking one drink, but they’re actually having two or three.

“People who drink more heavily should be concerned and should seek medical counselling for assessment of whether they need assistance with stopping alcohol use or if they have any damage as a result of long-term alcohol use.”